Sitting pretty. Day built all forms of custom furniture. Here, we see a settee with rolled and carved arms.

This black, antebellum-free man was North Carolina’s most successful cabinetmaker.

My introduction to Thomas Day came in 1998 on a shopping trip to High Point, N.C., for a bed. I stumbled across a reproduction of an antique piece that had soaring mahogany posts supporting a tester that authoritatively defined the space that the bed occupied. A floating headboard countered this effect. I was awestruck.

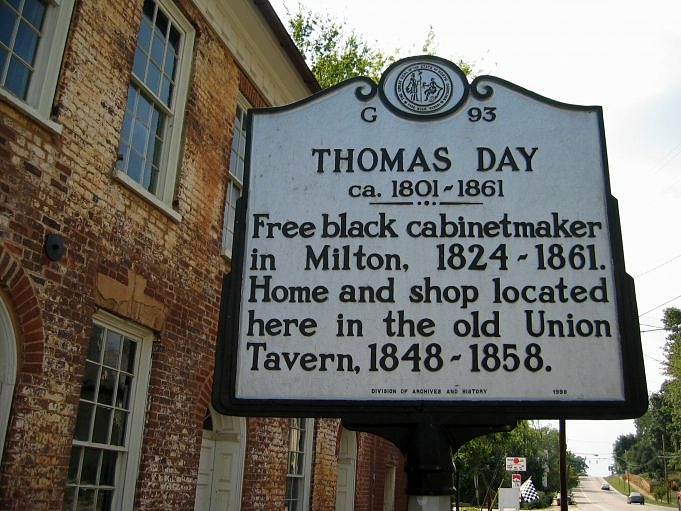

According to the description, the piece was made by Thomas Day (a North Carolina black cabinetmaker who was freed during slavery time and owned the largest cabinetshop in North Carolina). I was fascinated.

A Touchstone In Black History

I had always dreamed of doing 18th-century woodworking, but I didnt know the trade was one in which African-Americans were traditionally involved. Thomas Days work is a good example of this. Even though I didn’t purchase the bed, my world was expanded. Instead, I made a replica of the bed as my first woodworking project. Then I started to research the original craftsman.

Life-changing inspiration. This reproduction bed, built by the author from recycled pine, was based on a piece by 19th-century Master Cabinetmaker Thomas Day.

Thomas Day was born in Petersburg, Va. around 1801. His parents were both free and his family had been free for many generations. Thomas and John Day Jr. were Quakers and apprenticed under their father who was a master cabinetmaker.

The Thomas Days story cannot be told without looking at his brother, a cabinetmaker. John Day Jr. was disillusioned by the possibility of fair treatment as the country’s racial climate declined. He decided to leave the United States, a country that he dearly loved. Following his religious convictions, John Day became a Baptist, and went to Liberia as a Baptist missionary and eventually became the first chief justice of Liberias supreme court.

Careful Positioning In Society

Thomas Day chose a quite different route. Through his character strength, creative genius, and careful positioning in white society, he sought safety and security for his family.

Southern charm. This ladies bureau, which Day designed for the governor’s wife, featured one of his trademark scrolled motifs.

Day made a point of covering as much of the market as he could, and kept up with the latest styles. Day produced work in Gothic revival and Louis XV styles, as well as vernacular. He was well-respected by the governor and other members of the elite society. For them, he designed house interiors. More than 80 interiors can be identified as Days’ work to date. This is largely due to the distinctive newel posts or mantels that he used. Day was also skilled in stained poplar and pine, as well as oak and oak for the lower market. He also made coffins and provided transport to the cemetery.

To help alleviate the legal restrictions to his rights as a citizen, Day forged judicious relationships with white society. He specialized in providing the most fashionable furniture to the most powerful members of white society. He attended the Milton Presbyterian Church and made the pews for the church with the stipulation that he be allowed to sit with the white congregation. Day was also a slave owner, which earned him trust and acceptance by his white patrons.

Simple elegance. This simple cradle by Day has none of the distinctive carving of much of his work, but the elegant lines and curves appeal.

Days ownership of slaves is a thorny issue, and there is conflicting evidence about what he believed. We know that Day was able to keep his prices competitive by employing slave labor. We also know that Day was educated by Quakers who engaged in apprenticing slaves with the idea of their being eventually freed and prepared to earn a living. Did the Days slaves work as shop laborers, apprentices, or master cabinetmakers in their trade? They were allowed to purchase their freedom. We don’t know the answer, but further research may help.

To further muddy the picture, we know that Day sent his three children to what was considered a flaming abolitionist boarding school. Scholars are currently reviewing evidence to prove that Day was present at an abolitionist meeting held in Philadelphia. Day’s life and livelihood, as well as those of his family, would have been at grave risk if he had done so and Milton was informed.

A distinctive look. In addition to building furniture, Day built interior woodwork pieces for the homes of important clients. His distinctive mantels have helped identify more than 80 examples from his interior work.

His efforts to give his family a certain level of freedom were successful on several fronts. He married Aquilla Wilson in 1830. She was a Virginian. The state laws forbid blacks from entering North Carolina. However, citizens of Milton successfully petitioned to change the law. Day was also allowed to travel anywhere in the country and within the state. His children lived outside of North Carolina for extended periods of time while they were in school. All of this was outside the bounds of the law.

Sad Ending

Days’ professional and personal success was not enough to save his business. One in three businesses collapsed in 1857 due to a national bank crisis. Day also had difficulty collecting money he owed for the purchase of a steam engine that he purchased to help his business.

His health was also failing and he couldn’t keep up with the many orders required to keep his business afloat. In 1859, his business was declared insolvent. Although his son was able pay the debt in 1864, Day died in 1861. Day didn’t live long enough to see the business that he had built recover.

A Legacy In Wood

The works that Day left behind range from the mundane to the avant-garde. Day took popular patterns and forms and changed them with his own designs. His work is distinguished by his flowing lines and fluid shapes, as well as the decisive use of negative spaces.

Some suggest that Days creative genius was the result of his using woodworking as an outlet to express the isolation and frustration he felt living in the antebellum South. Others have suggested that it is his African heritage expressing itself. Still others say that until we further explore the African-American artistic aesthetic, we wont know. They are probably all right, I think.

An Education And Inspiration

Day and his work have been a part of my life for ten years. Now, I interpret Day’s work for the Thomas Day Education Project as well as various museums and historical sites.

I appreciate Day because he challenged many of my preconceptions and has caused me to stretch my knowledge base. Because of Day, my definition of what a cabinetmaker looks like has changed. Because of Day, my definition of good furniture has changed. Because of Day, I was inspired to follow my dream of doing period woodworking with a focus on Southern pieces.

Every piece of furniture we copy is a reflection on the lives and times of cabinetmakers. Pay attention to those stories; they have much to offer. And their stories just may help you revise your own.

Additional ReadingThomas Day: Master Craftsman and Free Man of Color, by Patricia Marshall and Jo Leimenstoll, takes an in-depth look into 160 pieces of furniture and architectural woodwork produced by Thomas Day.

Jerome is a historic interpreter, furniture maker, dairy farmer, quilter and upholsterer who lives in Mebane, N.C.

Product Recommendations

These are the tools and supplies we use every day in our shop. Although we may be compensated for sales made through our links, these products have been carefully chosen for their utility and quality.